By Mary Taylor Simeti for the Financial Times.com

In Sicily, there is no escaping history. Turn over a stone and you find a fragment of Byzantine pottery; ask a few questions about your favourite pastry and you are treated to a saga of monasteries and mayhem.

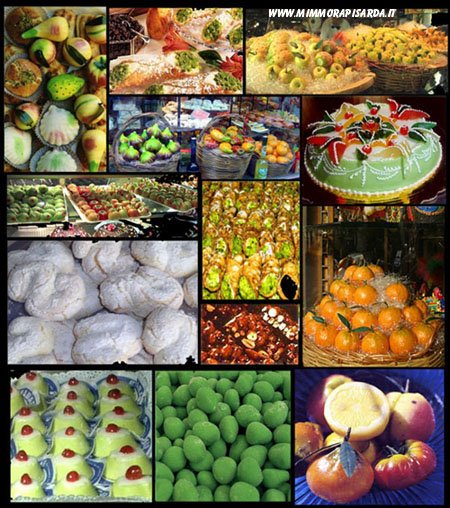

I had thought to write a straightforward description of the ravazzata, a pastry specific to the town of Alcamo where my husband grew up. I wanted to praise the discreet charm of these round, patty-shaped pastries, the measured sweetness of the ricotta filling within an unassuming exterior of golden crust. They are as distant from the rich and gaudy confectionery of Palermo - the cannoli and the cassatas studded with candied fruit - as the convent churches of Alcamo, hiding exquisite stuccos by Giacomo Serpotta behind simple stone exteriors, differ from the glittering, colourful mosaics of the Arab-Norman churches in Sicily's capital.

The consensus of opinion in Alcamo is that the best ravazzate are found at Cafè Napoleon, a bar and pastry shop on the Corso Stretto, the leg of the main street that narrows as it passes through the medieval part of town. But that is as far as I could get: no one could tell me if the ravazzata had been conceived in the kitchen of a commercial pasticceria or, whether like so many Sicilian pastries, it was the invention of some ingenious nun. Nor could anyone explain to me the etymology of its name.

A Sicilian pastry without a history - impossible! I turned for answers to a local historian, an ardent student of Sicily's gastronomy. "The ravazzate of Alcamo? Why, they began in 1887," I was told. I was bowled over by such unexpected precision, rare in a field where most of the artefacts have been either eaten or composted.

It appears that 1887 was the year in which a certain Signor Albanese returned from exile in South America (whether this exile was imposed by the judiciary or by the local mafia is not entirely clear to me) and opened a bar called Cafè do Brazil on the main street of Alcamo. He hired as his pastry chef Giuseppe Dattolo, who had been working as a doorkeeper for the Benedictine convent of San Martino in Erice, a medieval town perched high on a mountain some 30 miles west of Alcamo, still famous today for its pastry-making tradition. Dattolo and his wife had run errands for the nuns and had helped them in the kitchen, where they made pastries to sell in order to support themselves (religious orders in Italy had their properties confiscated after the Unification of Italy in the 1860s, and the monasteries were in a bad way). But Dattolo had been diagnosed with weak lungs and was advised to leave the cold, damp heights of Erice.

There is no way of knowing whether Dattolo continued to make the ravazzate for the Cafè do Brazil in the exact same fashion that the nuns of San Martino made them or whether he perfected them. Certainly they had evolved: the name ravazzata, the historian told me, comes from a word meaning leftovers - in Palermo, in fact, it is the name of a savoury street food made from stale bread - and indicates that they were originally fashioned from the scrapings and leavings of other pastry-making, a common trick in frugal nunneries. In any case, they were excellent, and the café prospered and became Alcamo's leading pastry shop, so much so that at the end of the great war a certain Signor Rubino decided to open a rival shop on the Corso. With promises of higher pay, he lured Dattolo from the Cafè do Brazil, which went into a decline and eventually folded. Albanese, upset by this turn of events, took revenge by chopping down Rubino's vineyards, a fairly common form of vengeance in these parts. Albanese went to jail.

It was Rubino's turn to prosper. His establishment changed hands and names through the decades, and although most middle-aged Alcamesi still tend to call it Sanacore, in the 1980s the current proprietor renamed it Cafè Napoleon. The excellence of the wares has not changed, however, and it is even today the best place to try a ravazzata, especially in the morning when they are still warm from the oven.

Mary Taylor Simeti is the author of several books on Sicily including 'Pomp and Sustenance: Twenty-five Centuries of Sicilian Food'

In Sicily, there is no escaping history. Turn over a stone and you find a fragment of Byzantine pottery; ask a few questions about your favourite pastry and you are treated to a saga of monasteries and mayhem.

I had thought to write a straightforward description of the ravazzata, a pastry specific to the town of Alcamo where my husband grew up. I wanted to praise the discreet charm of these round, patty-shaped pastries, the measured sweetness of the ricotta filling within an unassuming exterior of golden crust. They are as distant from the rich and gaudy confectionery of Palermo - the cannoli and the cassatas studded with candied fruit - as the convent churches of Alcamo, hiding exquisite stuccos by Giacomo Serpotta behind simple stone exteriors, differ from the glittering, colourful mosaics of the Arab-Norman churches in Sicily's capital.

The consensus of opinion in Alcamo is that the best ravazzate are found at Cafè Napoleon, a bar and pastry shop on the Corso Stretto, the leg of the main street that narrows as it passes through the medieval part of town. But that is as far as I could get: no one could tell me if the ravazzata had been conceived in the kitchen of a commercial pasticceria or, whether like so many Sicilian pastries, it was the invention of some ingenious nun. Nor could anyone explain to me the etymology of its name.

A Sicilian pastry without a history - impossible! I turned for answers to a local historian, an ardent student of Sicily's gastronomy. "The ravazzate of Alcamo? Why, they began in 1887," I was told. I was bowled over by such unexpected precision, rare in a field where most of the artefacts have been either eaten or composted.

It appears that 1887 was the year in which a certain Signor Albanese returned from exile in South America (whether this exile was imposed by the judiciary or by the local mafia is not entirely clear to me) and opened a bar called Cafè do Brazil on the main street of Alcamo. He hired as his pastry chef Giuseppe Dattolo, who had been working as a doorkeeper for the Benedictine convent of San Martino in Erice, a medieval town perched high on a mountain some 30 miles west of Alcamo, still famous today for its pastry-making tradition. Dattolo and his wife had run errands for the nuns and had helped them in the kitchen, where they made pastries to sell in order to support themselves (religious orders in Italy had their properties confiscated after the Unification of Italy in the 1860s, and the monasteries were in a bad way). But Dattolo had been diagnosed with weak lungs and was advised to leave the cold, damp heights of Erice.

There is no way of knowing whether Dattolo continued to make the ravazzate for the Cafè do Brazil in the exact same fashion that the nuns of San Martino made them or whether he perfected them. Certainly they had evolved: the name ravazzata, the historian told me, comes from a word meaning leftovers - in Palermo, in fact, it is the name of a savoury street food made from stale bread - and indicates that they were originally fashioned from the scrapings and leavings of other pastry-making, a common trick in frugal nunneries. In any case, they were excellent, and the café prospered and became Alcamo's leading pastry shop, so much so that at the end of the great war a certain Signor Rubino decided to open a rival shop on the Corso. With promises of higher pay, he lured Dattolo from the Cafè do Brazil, which went into a decline and eventually folded. Albanese, upset by this turn of events, took revenge by chopping down Rubino's vineyards, a fairly common form of vengeance in these parts. Albanese went to jail.

It was Rubino's turn to prosper. His establishment changed hands and names through the decades, and although most middle-aged Alcamesi still tend to call it Sanacore, in the 1980s the current proprietor renamed it Cafè Napoleon. The excellence of the wares has not changed, however, and it is even today the best place to try a ravazzata, especially in the morning when they are still warm from the oven.

Mary Taylor Simeti is the author of several books on Sicily including 'Pomp and Sustenance: Twenty-five Centuries of Sicilian Food'

No comments:

Post a Comment