Sicily has a serious plague.

This island claims a number of victims every summer: It is a cruel land with no mercy, even for the bravest visitor. It is the syndrome that afflicts the entire island. You know what I am talking about. The syndrome of Sicilian Ma...gnificence, that leaves every tourist stunned by the breathtaking scenery, delicious meals and a heavy dose of history.

Sicily made me fall in love with Italy all over again. Though I'd heard raves about the food, every meal - indeed, every morsel I ate - exceeded my expectations.

The island's fat, green and brown olives burst with juice. Sweet, plump oranges are sold with leaves and twigs still attached. I've had fish on the coastlines of four continents, but I've never tasted pesce spada (swordfish) or dentice (sea bream) as fresh as this, almost leaping from the sea onto my plate.

It's hard to think of more distinctive pasta, such as those I sampled at a restaurant called

Lo Scudiero on Via Turati in Palermo. Two dishes that are emblematic of Sicily are pasta alla Norma with tomato, eggplant, ricotta and basil, and pasta con le sarde, a tangle of fresh sardines, raisins, pine nuts, olive oil, wild fennel and bread crumbs.

Then there's the wine. In recent years, Sicilian wine has been the island's greatest ambassador. The reds, such as earthy and ripe Nero d'Avola, and the whites, like Grillo, are bright, floral and citrus-y. Many of them cost less than $10.

Sicily is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea and has more land planted with vines than any other Italian region. To give you an idea of how much wine it makes, consider that Sicily alone produces nearly as much as all of Australia.

One of the biggest wineries in the region, Feudo Arancio, is open to the public. To get to the winery's vast, hilly holdings in southwestern Sambuca di Sicilia, we drove past orange, lemon and olive groves and fields of artichokes. A backdrop of craggy mountains, palm trees and prickly pear cactuses made me think of the American Southwest.

Winemaker Calogero Statella, 29, was on hand to lead us through a complimentary tasting of his wonderful Nero d'Avola and Grillo wines, as well as Hecate, a honeyed dessert wine. He also makes fine international varieties like Syrah, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay.

After visiting the vineyards and state-of-the-art winemaking facility, we drove a short distance to the Temples of Selinunte, a nearly 2,700-year-old archeological park perched on the sea. The colossal acropolis rivals the one in Athens.

In 409 B.C., Hannibal and his Carthaginian warriors sacked Selinunte. Earthquakes smashed up the rest. Excavations have been underway since the 1950s, but there's a long way to go before the eight Doric temples are rebuilt. The ruins are nevertheless stunningly beautiful.

Other than food, wine and archeological digs, Sicily is famous as the birthplace of the Mafia. It's said La Cosa Nostra isn't what it used to be, except perhaps in rural areas. But for a "Godfather" fix, visit

Palermo's ornate Teatro Massimo opera house, where Sofia Coppola, as Michael Corleone's daughter, was slain on the steps in "The Godfather: Part III."

At first glance,

Palermo seems lawless and treacherous. Drivers pay little attention to traffic lanes or stop signs. You have to hold on tight when you careen in a car from the airport through downtown, passing small trucks hauling artichokes and speeding brigades of Vespas. Curiously, I saw no accidents.

During a walking tour, we saw Baroque and Middle Eastern architectural influences. This melting pot of cultures was occupied by Greeks, Romans, Arabs and Normans, and later conquered by the French, Spanish and Italians.

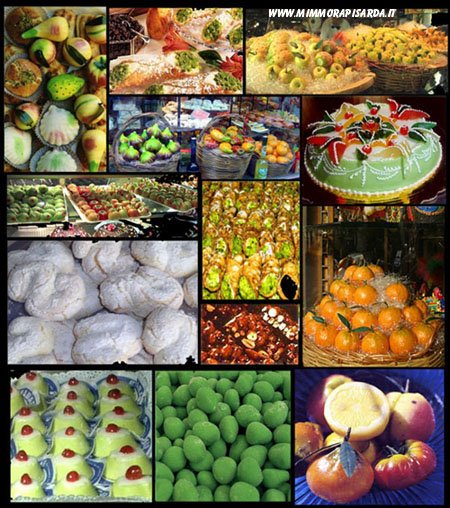

We also shopped at outdoor markets brimming with long-stalked artichokes, heaps of vivid spices, grassy-green olive oil, almond liqueur, capers packed in salt, magnificent oranges and briny olives. For snacks, buy

arancini (deep-fried risotto balls) and fresh Bronte pistachios wherever you see them.

In the middle of all these tastes, smells and sounds of hectic traffic, we came upon a giant crater roped off like a construction site.

"What happened here?" I asked our guide, thinking an earthquake had recently struck.

"It was bombed," she said.

"By who?"

"The Americans," she said.

"Sorry," I said, remembering that Italy was not our ally in World War II.

She shrugged, not holding it against us. Americans don't seem to be holding any grudges against Italy, either. My flight out of New York to Milan was packed with Americans, many of whom told me they were making connections to

Palermo.

Perhaps because Sicily seems more exotic and undiscovered than other parts of Italy, tourism is up.

Other than their

driving habits, it's the most relaxed society I've come across. Clusters of friends and family sit and talk and laugh on street corners, in no rush to get back to work or chores.

Sicily is Old World Italy, a place bent on tradition. Take the chocolate, for instance. In Modica, a southeastern town whose Baroque stone dwellings cling perilously to a mountaintop, the chocolate-making method hasn't changed in centuries. Cocoa and sugar aren't melted so much as beaten into submission, leaving a bar that looks smooth but has a crunchy, granulated, powdery texture that melts on the tongue. No butter or milk is added.

Hotels are more up to date, though, often offering free Internet service in the lobby. In

Palermo, I loved the shabby-chic Excelsior Palace (

http://www.excelsiorpalermo.it/ ) for its Belle Époque elegance and swan-necked Murano chandeliers.

In the gorgeously Baroque southeastern town of Ragusa, we stayed at the enchanting Locanda Don

Serafino in the historic Ibla district.

Rooms are like lavish, white-walled caves. The hotel's stylish restaurant is housed in old horse stables, serving specialties like lasagnette with cocoa and ricotta, or rabbit with bacon and Bronte pistachios.

I spent less than a week in Sicily and wished I had a month. After driving around the island, I flew out of the Catania airport and overheard fellow travelers rhapsodizing about the volcanic splendor of Mount Etna, the temples at Agrigento, and the towns of Messina, Noto, Syracuse and Cefalù.

At the Alitalia ticket counter, Italians were shouting and waving, jostling for position. I finally fought my way to the front and presented my passport, afraid flights were canceled.

"What's wrong?" I asked the ticket clerk, gesturing at the chaos.

"It's nothing," she said with a shrug, with a nonchalance typical of Sicily.